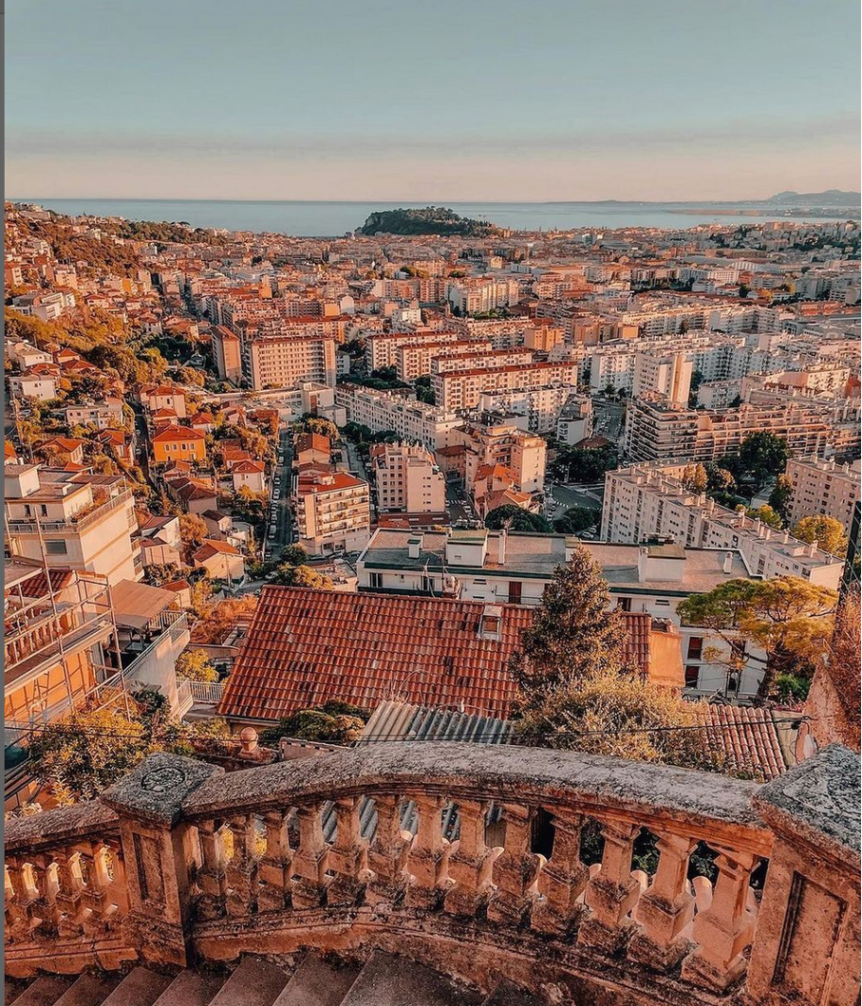

The City of Nice in the South of France is the site of some of the most important Jewish heritage in Europe. Not only was Nice a refuge for Jews during the Middle Ages (13th, 14th and 15th centuries) when England, France, Spain, Portugal, Provence, parts of the former Savoy and others expelled Jews, but it was also considered the last refuge for Jews during the Second World War. As a tourist based city whose hotel rooms, casinos and restaurants were suddenly empty at the start of the war, enterprising individuals realized that by attracting and protecting Jews from around Europe, they could restart the city’s economy and even prosper in the turmoil. And they came in the thousands.

In the Middle Ages, we often hear of certain towns in Provence, such as Avignon and Carpentras, that were a refuge for Jews as they were protected by the Popes, but Nice was the only real city in France in which Jews were allowed to live and at various times, strongly encouraged to come. An examination of the medieval archival records shows Jewish bankers were particularly active in building and sustaining the region, but medieval Jews in the region were also involved in many industries, such as salt, coral fishing used in jewelry, textiles and medicine.

We have records of Jews in the region from Roman times, back to the second century of the common era. Later, Jews from Provence, England, France, Spain, Portugal, Rhodes, Gibraltar, Amsterdam, Chambéry, Tunisia, Algeria and many more arrived in Nice as their final destination. Jews in the city even had their own language, Judéo-Nissart, a mixture of the Nissart dialect of Occitan and Hebrew. When visiting the city it helps to recall that it was only in 1860 that Nice became permanently attached to France. Before that Nice was part of the Savoyard States, a country that no longer exists and which became absorbed eventually by the modern states of France, Italy and Switzerland.

The first medieval Jewish street or locked ghetto in Nice dates back to 1391 and the gates were finally unlocked permanently only in 1860. Under the city in the tunnels of the ghetto, we find carvings on the walls of Jewish symbols.

The Jewish cemetery in Nice dates from 1784, making it one of the oldest in Europe and unusually includes both Ashkenazi and Sephardi tombstones as well as others in eight different languages, reflecting the attraction of Nice for some of Europe’s most wealthy individuals. Here we can trace the diaspora back centuries to understand various Jewish groups, such as Russian Jews in the time of the Czars, Jews of the Avignon Popes (from Medieval times), Spanish and Portuguese Jews or Jews from the Ottoman Empire. Nice, like America was an important destination in the late 19th century for those who sought to escape the pogroms of Eastern Europe.

In the 1940s, Nice was the last place in France where one could find kosher food, to see people dressed in their traditional Jewish garb and hear Yiddish freely spoken in its streets, as the city continued to support a Jewish life. Although it was initially in the unoccupied zone or part of Vichy France, it fell under Italian control in 1942. In fact, Nice was the prize which Mussolini hoped to get by his participation in the war on the side of the Germans. Yet the Italian occupiers did not harbor the same hatred for the Jews as the Nazis and in Nice, the Italians actively worked to protect the Jews again and again refusing to deport the Jews in Nice and posting armed soldiers outside the synagogue. The Hotel Roosevelt housed the various Jewish rabbinical congresses. Yet not much about the Jewish history and heritage in Nice in known by the general public as finally, in September 1943, with the capitulation of the Italy army, Nice became the primary focus for the Nazis and the brutal Alois Brunner, Adolf Eichmann’s right hand man, to continue their deportation and murder of Jews. A city at the time with a total population of 250,000, had by September become the home to as many as 40,000 Jews, housed openly in the city’s hotels and hidden in apartment building through the city. Efforts were being made to transport the city’s Jews to Palestine when Italy fell to the Allies and the Nazis suddenly and unexpectedly moved south to fill the Italian void. This German invasion spawned various networks to hide and relocate Jews, such as the Réseau Marcel, to rescue the Jews children. Many of these protective networks were led by the Bishop of Nice with the active support of the Reform Church. This final period of the war has left its mark throughout the city, and while much of Jewish history in Nice is unmarked by plaques or other commemorative items, an informed visit will show the city and its Jewish heritage remains untouched. Unlike so many cities in Europe who had a rich Jewish culture that was destroyed in the war, Nice was never bombed and its Jewish heritage remains intact.

Many places in Europe which were important to Jewish heritage have now become only museums and remembrances of the past, yet Nice has an active Jewish population estimated at around 30,000 which includes Nice, Cannes, Juans-les-Pin and Monaco. A minyan in Nice is held three times a day.

The majority of the Jewish community are Sephardi, coming mainly from Algeria, Tunisia with their independence in the 1960s and the Ottoman Empire, although there is an Ashkenazi synagogue. Here there are all the kosher facilities one may need such as schools, restaurants, bakeries and groceries and they continue to multiply. Incidence of antisemitism are rare and the mayors and city governments in Nice and Cannes, for example, are very supportive of Israel and the Jewish community here.

Robert Levitt is a historian of Jews in Provence and the County of Nice. He conducts private tours of Jewish Nice and elsewhere in Provence for Via Nissa (www.vianissa.com)