While working in the archives of the Alpes-Maritimes in Nice, sorting documents from a 20th century politician, I ran across a letter from a constituent which gripped my attention like no other. The letter was one of palpitating fear. You could almost feel the sweat dripping with each word as the writer, processing the horror of his circumstances, tried to convey to the Vichy Councilman that he was about to be deported by the Gestapo. They were convinced he was Jewish, when in actuality he was not. Due to the war in North Africa (the Allied Armies were advancing towards Sicily), he could not obtain his original documents and now he had nowhere left to turn. Perhaps by this time, Jews had come to know or at least envision what was in store for them if they were caught, but this non-Jew spoke of the terror of the unknown: first realization of what Jews had been feeling for several years or perhaps even centuries. It was the sort of letter which shook me from a stupor to realize that I had moved to one of the most important Jewish cities of WWII, the last refuge in Europe for Jews. This letter drew me to study the subject of Jewish Nice. As a Medieval historian, reader of Latin, and with a great deal of archival experience, I began to discover and explore the extraordinary rich Jewish heritage in the city of Nice.

You might know that Nice became part of France only in 1860. Before that, and since 1388, it had been a city that was part of the County of Savoy, which was ruled by a Duke in Torino. It was not long after becoming part of this authority that in 1430, a ghetto “Juiverie” was imposed on Jews by its masters in Torino and in the Latin statutes, we can read that Jews were mandated to wear a yellow star on their clothing. The idea was to impose a border against ideas and practices declared to be profane, to posit a separation between and clearly establish who was and who was not a Christian as well as to marginalize the Jews. In this period and even until the 19th century, it is important to realize that Judaism did not relate to what we now call a “religion,” which separates cult from culture, but to a whole set of lifestyle practices which the ghetto in Nice allowed to flourish. But the authorities in Nice apparently did not listen, because 18 years later, a follow-up letter was sent to those authorities castigating them for their failure to separate the Jews of Nice into an isolated area locked at night. Strangely however, while in Torino the government was provoking the Jews, in that same year of 1448, the city of Nice gave its banking franchise – known as a Casana – to a Jewish banker named Bonnefoy de Chalons, “Jew of Savigliano”, seemingly after having tried the Christian bankers unsuccessfully. Reading the Latin contract, I could see that Bonnefoy had full rights to come and go as he wished and to live wherever he pleased which made no sense if a Jewish ghetto had been imposed by the city the same year.

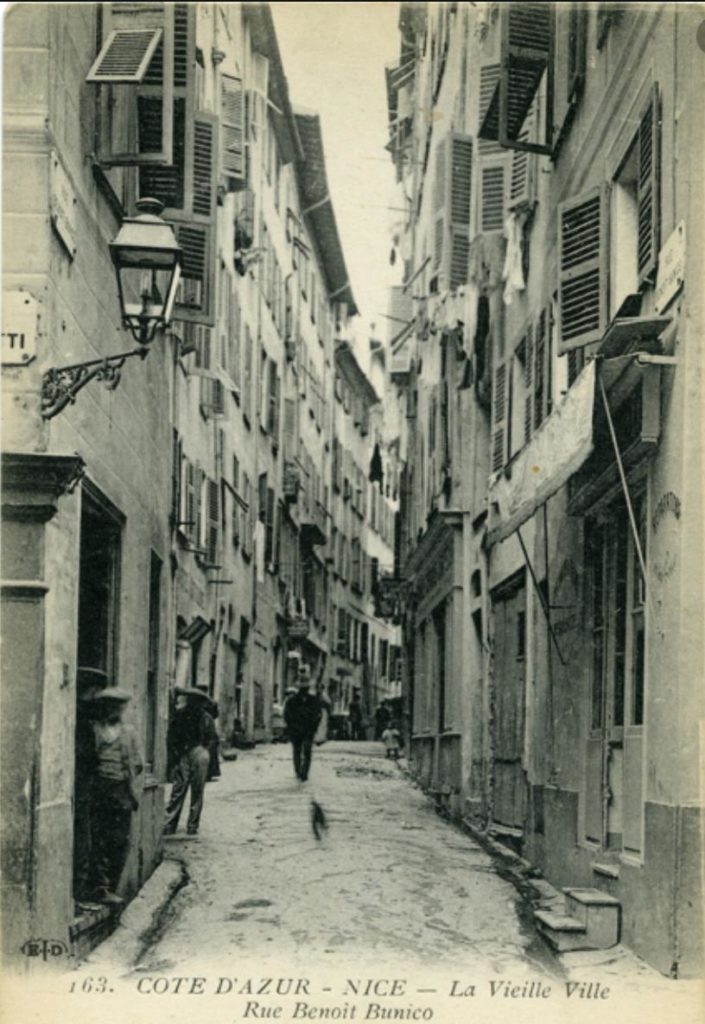

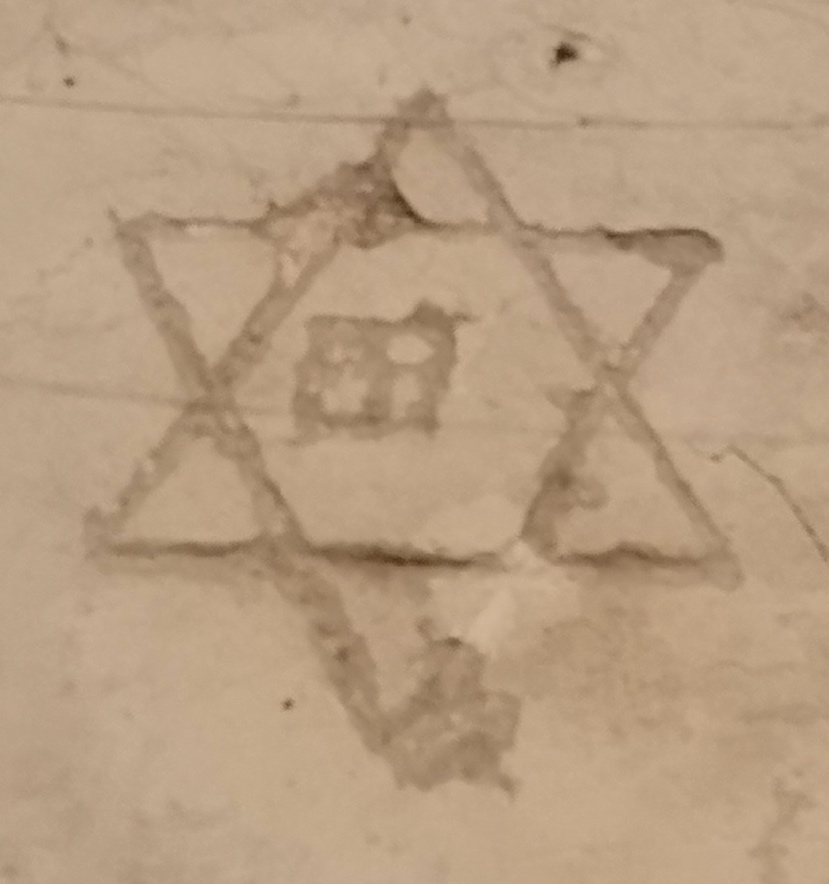

Whether a ghetto was ever actually imposed in Nice during the Medieval period remains an outstanding question in my mind and progress in the discovery of recondite documents from Nice’s past is an ongoing process. What we know is that in 1733, the ghetto in Nice became a reality. Permission was given that year to designate a synagogue on the third floor of a building owned by the Catholic brotherhood Pénitents Noirs and that there was a mikve in the basement. It was prohibited at the time to build any ostensibly religious building which was not of the Catholic faith, so the synagogue had to be integrated into the present architecture. The ghetto is located in Old Town Nice and the buildings on at least one side of the street had underground tunnels to the adjacent street, rue Droit, which would allow the Jews to come and go when they chose. In 1750, the obligation for Jews to wear a badge was formally abolished, and it is believed the ghetto in Nice was as well as. Known as the rue de “lou Ghet” or “la gudecca” in the local Nissart language or previously “rue de l’Arc” and “rue de Statuto” in French, the legal restrictions on Jews were ended and they were emancipated in 1848, advocated by the progressive municipal counselor, Benoit Bunico (1801-1863) . What I did not expect and had not read about was that those same tunnels likely housed Jews during the World War II. In a private cellar, I discovered a Star of David and a Menorah as well as communist symbols and one symbol which I continue to research, engraved into the walls.

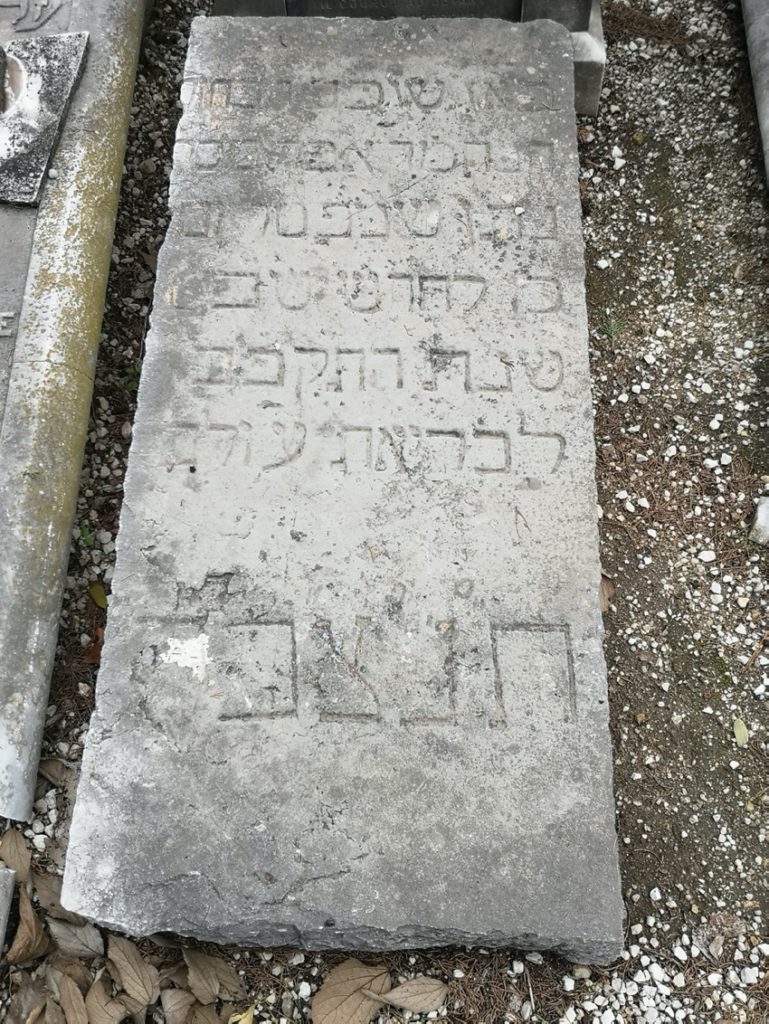

The Jewish cemetery, opened in 1783, contains the tombs of the previous Jewish cemetery which was forced to relocate on the demand of a monastery in the immediate vicinity which wished to enlarge its accommodation. It lies on a beautiful piece of land overlooking the city of Nice. It, by itself could tell the history of Jewish families that came to Nice, which I found spelled in a variety of ways (Nizza, Niza, Nica, Nissa, Ніцца, Ηίκαια, Nicea, Nicaea, Nisa, Ницца). There are gravestones in French, Hebrew, Polish, Italian, Russian, English and German. They were born in Kiev, Vasylkiv, Warsaw, Kishinev, Mariupol, Kherson, Odessa, Nikolaev, Kaunas, Berlin, St. Petersburg, Lwów, Radautz of Bukovina (Rădăuți, Romania), Algeria, Oran, Constantine, Taganrog, Constantinople, London, Rangoon, Cairo and Johannesburg. As I have dug deeper into the history of individuals buried there, those who lived an “unhistoric” life and rest in unvisited graves, I found Jews whose Sephardic ancestors were chased in the Medieval period from England, Spain, Portugal, North Africa, the Middle East and many other places. By researching those buried in the cemetery, one can almost piece together the pattern of movement of Jewish communities throughout Europe, and it is this research will I actively pursued. Well-known names like the jeweler Alfred Van Cleef (1872-1938), whose ancestors likely escaped persecution in Germany, would go to the Netherlands, a Protestant country in the 16th century, which welcomed Jews, useful for their commercial capabilities, worldly ambitions and unlimited horizons. Later, when Napoléon occupied the Netherlands, many Jewish families in the Netherlands came to France. Others like the Poliakoff family were Russian Jews who built more than 20% of the Russian railroads in Czarist Russia. They eventually fled to Nice as well and were instrumental to the city’s development.

Although some sources state that the oldest stone slab or grave marker in the cemetery dates to 1540, so far, the oldest I have found is this one, dated 1762. As it pre-dates the present cemetery, it means that this slab and others were transported from the ancient fifteenth century cemetery to the present one. This provides a historian like myself the opportunity to seek the origins of Jews in Nice. With gravestones and archival records speaking of Jews in the fifteenth century, I can confirm at least those origins, even though some historians point to Jews in the region as far back as the third century.

Yet the most extraordinary Jewish stories and which for a long time were never openly discussed were those that took place in the war years of 1942-1944. Nice, was initially part of the unoccupied part of France, known as Vichy France.

In August of 1942, the Germans required the French to begin a roundup of Jews and like so many other places in the Vichy French zone, this process began in Nice. But with the Allied armed forces moving through North Africa, the unoccupied zone became occupied with German and the Royal Italian Army occupying the southern portion of France. On November 11, 1942, Nice fell under the jurisdiction of the Italians, who refused to hand over Jews to the Germans for deportation.

The Italian zone initially consisted of French departments on the Eastern border with Italy. These areas became a Noah’s Ark for hunted Jewish refugees and their population rose significantly. The Italians actually allowed these foreign Jews to regularize their situation, provide Jews, who were arriving from throughout Europe, with housing and ration cards. Many had left their homes with next to nothing except perhaps what they could carry and some spoke only their native tongues, such as Yiddish. However, as 1943 progressed, the Germans pushed the Italians to reduce their occupation zone and the safe territory for Jews was reduced to only the small area between Nice to the Italian border. Estimates that as many as 100,000 Jews crowded the city of Nice, filling up its hotels and available spaces. Some have suggested that well over 25% of the city population was Jewish at the peak in August 1943.

Yet the war raged on, and the Allied Armies rapidly gained more and more territory to where it was feared that the Italians would be taken out of the war. A plan was devised by an Italian banker named Angelo Donati (1885-1960), to hire ships to take the Jews in Nice to Libya and other parts of newly liberated North Africa. In fact, it was to be a three prong plan.

The Italians would sign an armistice agreement with the Allied Armies, they would in turn attack the Germans and the Jews were to be transported to safety in areas recently liberated in North Africa. But these plans failed because it was accidentally announced prematurely that an armistice was signed and the Germans rushed it to take over the Italian zone.

In September 1943, they brought to Nice the infamous Jew hater S.S. Alois Brunner Obersturmbannführer, known for wiping out the entire Jewish population of Salonika, Greece. With thousands of Jews recently arriving and having registered, they became easy targets of a brutal Nazi murderer and Nice reacted, hiding Jews and especially their children, working through resistance groups such as the Marcel Network, a group which took care of children left alone after the arrest of their parents and hid them in Christian institutions with false identity and ration cards. All this was an extremely dangerous task because if anyone was found hiding or helping Jews, they too would be deported to Drancy internment camp in Paris and then Auschwitz in Poland. It was in Nice that the family of Romanian born Serge Klarsfeld, who went on to becoming one of the most famous Nazi hunters, lived as a small boy, and the Hotel Excelsior which was taken over for part of 1943 as the headquarters for a military branch of the Nazi party (featured in the 2017 movie, A Bag of Marbles). In 1951, a memorial was constructed in the cemetery in remembrance of the resistance and martyrs.

This traumatic period for Jews caused a “zone of silence” for many years and one of the reasons there were limited possibilities for Jewish Heritage tours. It is not a forgotten history, like in places Jews left long ago as we see in Eastern Europe, Medieval Spain or Portugal. Many of the residents here and their families had to live with the terror of daily fear of deportation, rape and some had survived Auschwitz to return. They didn’t want to speak of what had happened as it was too painful. Now, with time, the city has been open again to discussing what occurred there. A monument to the Justes was put up in 2014 to commemorate some of those who helped Jews during the war and in January 2020, a new memorial will be unveiled commemorating the more than 3,800 deportees from this region, taken first to Drancy internment camp in Paris and then the Auschwitz concentration camp in Poland, where over 1.1 million men, women and children lost their lives.

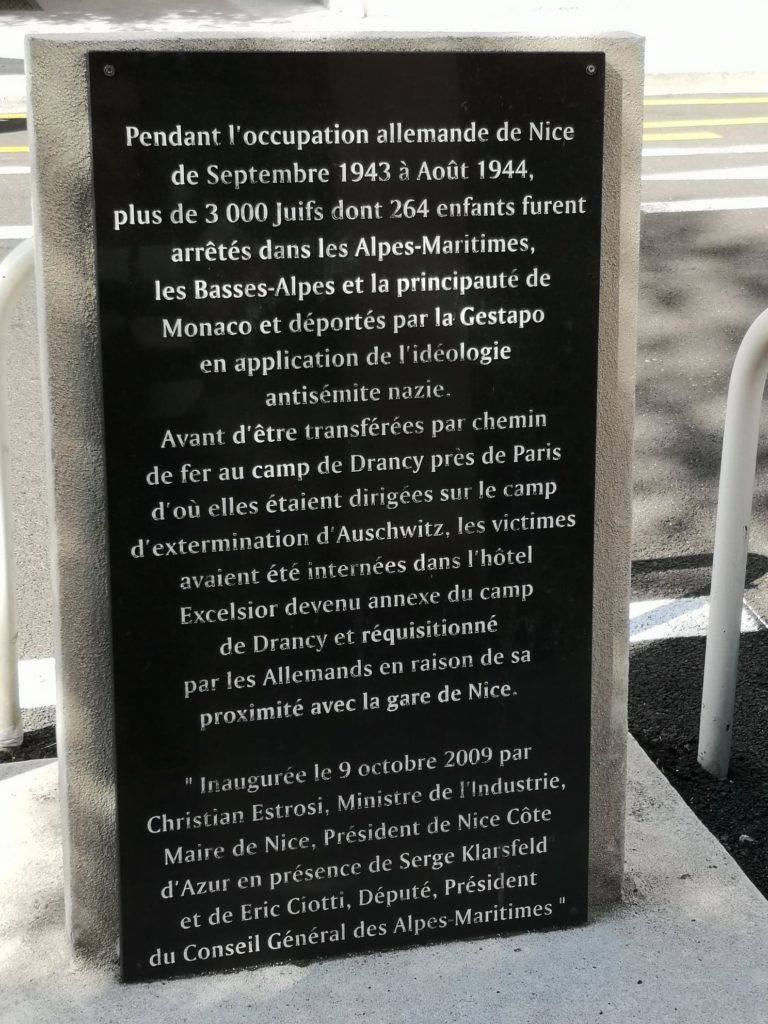

“During the German occupation of Nice from September 1943 until August 1944, more than 3,000 Jews, of which 264 were children, were arrested in the Alpes-Maritimes, Basses-Alpes and the Principality of Monaco and deported by the Gestapo, in applying the ideology of Nazi anti-Semitism. Before being transferred by train to the Drancy camp near Paris where they were then sent to the extermination camp of Auschwitz, the victims were interned in the Hotel Excelsior which became an annex of Drancy camp and requisitioned by the Germans due to its proximity to the Nice railroad station. Inaugurated October 9, 2009 by Christian Estrosi, Minister of Industry, Mayor of Nice, President of Nice Côte d’Azur in the presence of Serge Klarsfeld and of Eric Ciotti, deputy, President of the Governing Counsel of the Alpes-Maritimes.”

The Jewish heritage in Nice is not about places which “used to be” something else. Its Jewish heritage remains in full view, although it takes some interpretation to see and understand it. Today, two of the functioning synagogues date from the end of the 19th century. It has an active Jewish community where I have participated in learning both Judeo-Espanol or Ladino, the language of the Sephardic Jewish diaspora (Sepharad is the Hebrew name for Spain and Portugal) as well as Yiddish, the language of the Ashkenazi diaspora. It is a place where you can still appreciate the horror and fear in the story of a building being illuminated from outside, shortly after midnight, and the sound of the heavy boots of Gestapo soldiers racing up the stairs. Join me on a tour of Jewish Heritage in Nice.